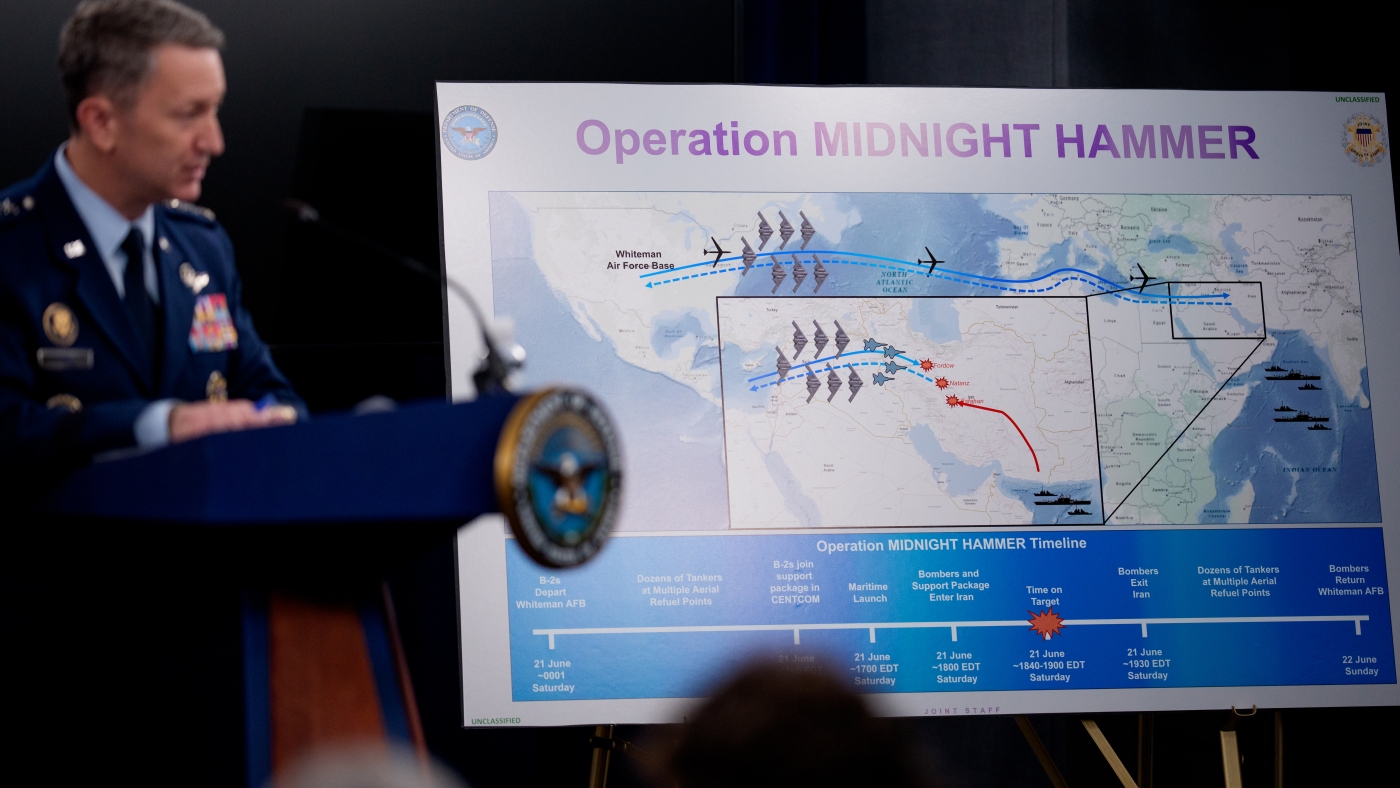

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Workers Air Drive Gen. Dan Caine discusses the mission particulars of a strike on Iran throughout a information convention on the Pentagon on June 22, 2025 in Arlington, Va.

Andrew Harnik/Getty Photographs

disguise caption

toggle caption

Andrew Harnik/Getty Photographs

The framers of the U.S. Structure lived in an age of muskets and messengers, when battle moved slowly and left time for Congress and the president to confer. However by giving Congress the ability to declare battle and the president command of the navy, they set the stage for lasting wrestle over U.S. forces.

President Trump’s determination to launch airstrikes on Iran’s nuclear services with out first consulting Congress has drawn sharp criticism from lawmakers who say the transfer bypasses their constitutional authority to declare battle.

Talking Monday on NPR’s Morning Version, Sen. Mike Kelly, D-Ariz., stated that whereas there’s little Democrats can do to drive the administration to hunt congressional approval, the president ought to nonetheless respect constitutional norms. “The administration ought to adjust to the Structure,” Kelly stated. “Historically, presidents have executed that. I do know lately, generally with sure actions, when it’s considered as defending the protection of our nation, presidents can act, after which they need to be capable of notify us.”

Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., was extra direct in his criticism. Showing Sunday on CBS’ Face the Nation, he stated: “America shouldn’t be in an offensive battle in opposition to Iran with no vote of Congress. The Structure is totally clear on it. And I’m so disillusioned that the president has acted so prematurely.”

So what does the Structure really say?

Article I provides Congress the ability “to declare Conflict, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Guidelines regarding Captures on Land and Water.” Article II, in the meantime, designates the president as “Commander in Chief of the Military and Navy of america,” giving the manager authority to direct the navy as soon as battle has been approved.

“I feel it is fairly clear that the framers thought that any time we had been going to be making the choice to go to battle with one other nation, that was going to be a call for Congress,” says Rebecca Ingber, a legislation professor at Cardozo Regulation Faculty in New York.

But presidents have lengthy despatched U.S. forces into fight with no formal declaration of battle. As an early instance of this, Stephen Griffin, a constitutional legislation professor at Tulane Regulation Faculty, factors to the Quasi Conflict, a restricted naval battle between the fledgling U.S. and its erstwhile Revolutionary Conflict ally, France. It passed off on the finish of the 18th century however there was by no means any formal declaration of battle between the 2 international locations.

That pattern accelerated after World Conflict II, pushed by a mixture of recent navy applied sciences and evolving world establishments.

“The creation of the atom bomb modified the sport,” says Griffin. Within the early republic, communications had been gradual and navy deployments took months. After 1945, nonetheless, “issues had been sped up,” Griffin notes. “You would wish generally an prompt response.”

He additionally factors to the affect of the United Nations, which the U.S. helped set up in 1945. The U.N. Constitution prohibits using drive by member states besides in self-defense or with Safety Council approval. Even within the U.S., that framework helped shift authorized discussions away from formal declarations of battle and towards ideas like “use of drive,” he says.

Critically, Griffin says, the Structure does not require Congress to problem a proper declaration of battle. What issues is legislative approval — resembling an authorization for using navy drive (AUMF). “The constitutional requirement is about legislative approval,” he explains, “not actually choosing up a doc that claims ‘Declaration of Conflict’ and signing it.”

Whereas the Korean Conflict didn’t have a proper declaration, the Gulf of Tonkin Decision — extensively regarded right this moment as a deceptive assertion of the info of a naval encounter between a U.S. destroyer and North Vietnamese gunboats — did draw the U.S. additional into the Southeast Asian battle. Handed it in 1964, that decision approved President Lyndon Johnson to take navy motion in Southeast Asia. President George H.W. Bush received an AUMF for the Persian Gulf Conflict in 1991. Through the 1999 Kosovo disaster, President Invoice Clinton launched a NATO bombing marketing campaign in opposition to what was then Yugoslavia with out congressional authorization.

Debate over these conflicts regularly noticed the legislative and government branches at odds. Within the wake of the Vietnam Conflict, Congress sought to claw again some authority by passing the the Conflict Powers Decision of 1973, which sought “… to satisfy the intent of the framers of the Structure … and insure that the collective judgment of each the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities.” The decision requires the president to inform Congress inside 48 hours of deploying U.S. forces into hostilities and to finish the deployment inside 60 days except Congress authorizes or extends it. It grew to become legislation after Congress overrode President Nixon’s veto.

Michael Glennon is a professor of constitutional and worldwide legislation on the Fletcher Faculty of Regulation and Diplomacy at Tufts College who was additionally a authorized counsel in the late Nineteen Seventies for the Senate International Relations Committee, the place he dealt with authorized points surrounding the Conflict Powers Decision.

“Vietnam grew to become the turning level for Congress as a result of their constituents had been being killed,” Glennon says.

Initially, he and others had been optimistic that the Conflict Powers Decision would appropriate the imbalance between Congress and the president and forestall one other Vietnam. As an alternative, the decision has been largely ignored by presidents of each events, he says. Over time, administrations have routinely sidestepped its necessities — informing slightly than really consulting Congress, and persevering with navy operations with out correct authorization.

Glennon believes the Structure “does prohibit the president from utilizing armed drive in attacking a rustic resembling Iran except there may be an assault on america or the specter of an imminent assault.”

That did not occur, he says, “and I conclude, subsequently, that this was unconstitutional,” he says.

However Glennon acknowledges that “usually talking,” the requirement beneath the 1973 decision to seek the advice of Congress has been complied with. “However in some circumstances, Congress has been knowledgeable [ahead of time] slightly than consulted. That is not what the Conflict Powers Decision contemplated.”

Ingber, of Cardozo Regulation Faculty, agrees. “Even this administration … is no less than nodding towards these necessities. Even Secretary of Protection [Pete] Hegseth stated, [the administration is acting] ‘in accordance with the Conflict Powers Decision.’ “

That modicum of respect for no less than a part of the decision underscores that it “is extensively thought of constitutionally justified beneath Congress’ ‘obligatory and correct’ energy,” Griffin says.

If the assault on Iran is really a one-off — because the administration contends — the necessity to get authorization from Congress for using navy drive is probably going pointless, he says.

However “if this turns into tit-for-tat with Iran, Trump ought to get an authorization. That will fulfill the Conflict Powers Decision — and strengthen his authorized place,” in accordance with Griffin.