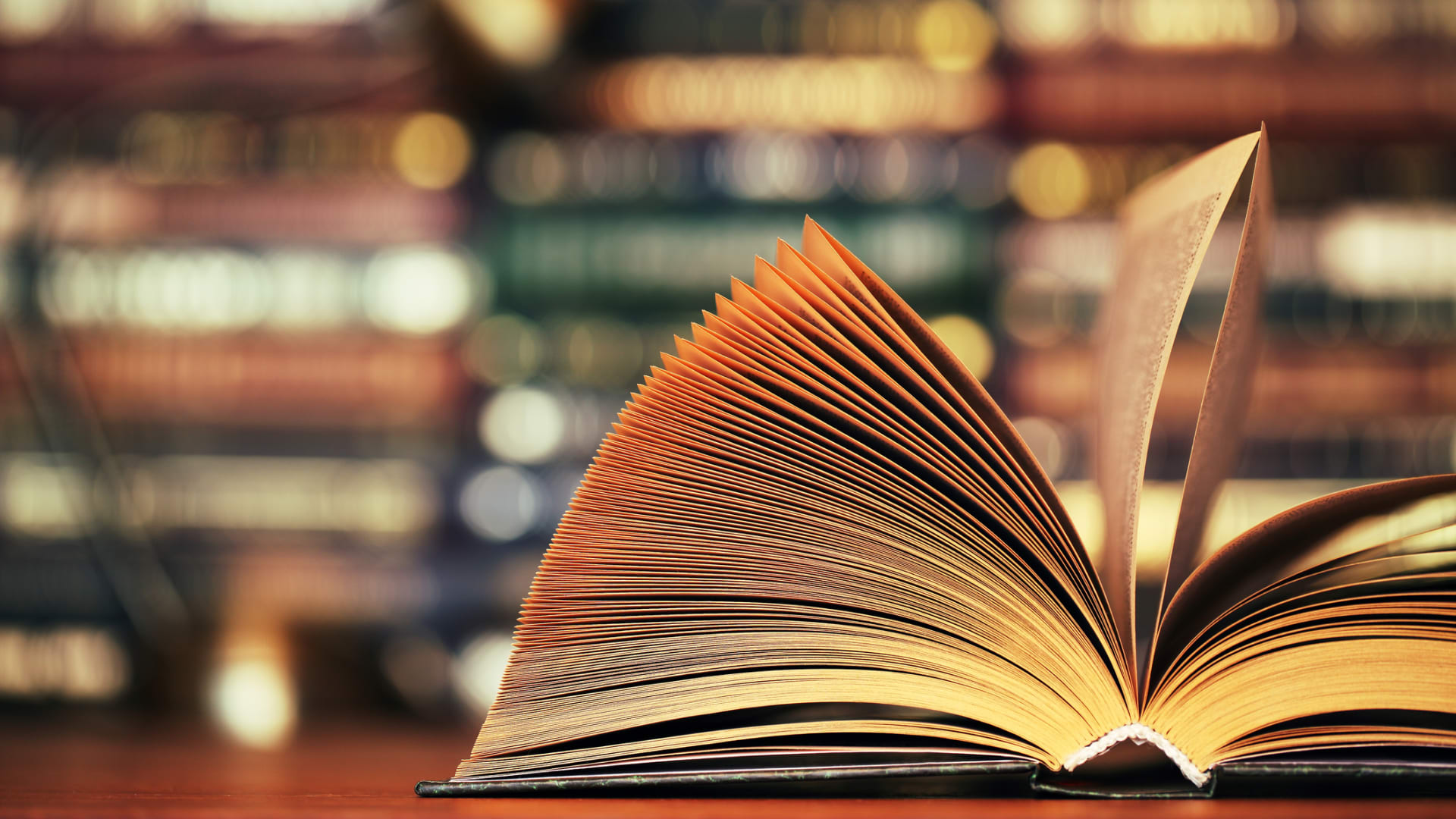

Various kinds of baklava are on show and being packaged at Gulluoglu, a store in Gaziantep, Turkey. Town has many outlets devoted to the candy pastry.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

GAZIANTEP, Turkey — When visiting this historic southern Turkish metropolis, it would not take lengthy to find its true ardour: baklava.

A lot in order that Gaziantep has turn out to be synonymous with the candy pastry, made from a number of layers of phyllo dough, full of nuts and soaked in syrup or honey.

Retailers throughout the town are adorned in inexperienced and gold — inexperienced for pistachios, gold for the dessert’s flakey crust. Acres and acres of pistachio groves encompass the town. Even on the airport, sculptures of the beloved seeds line the curbs outdoors the terminals.

Baklava shouldn’t be distinctive to Gaziantep, and the town would not declare its origins. The pastry is feted in native cuisines of many international locations, from Iran to Greece to Algeria. However no metropolis has made baklava right into a vacationer attraction, an enormous business and a public obsession fairly like Turkey’s Gaziantep.

NPR not too long ago toured the town — together with Mustafa Bayram, a professor of meals engineering at Gaziantep College — to seek out out: What’s it that has this place so entranced by this sticky delight?

The OG: Gulluoglu

Mustafa Bayram (heart), a professor of meals engineering at Gaziantep College, walks via the Elmaci bazaar in Gaziantep, taking a look at and speaking in regards to the totally different meals and substances on the market.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

The primary cease was a retailer in Elmaci bazaar, tucked between a 14th century mosque and outlets promoting dried peppers, eggplants and colourful spices. Gulluoglu is a quaint, slender store run by two brothers, 43-year-old Cevdet and 37-year-old Murat Gullu. They are saying they’re the sixth era of a baklava-making household, and boast that theirs is the oldest baklava store in Turkey, opened in 1871.

“Our prospects come right here with their grandkids and inform us that their grandfathers had introduced them right here to this store to eat baklava after they had been younger,” says Cevdet Gullu.

The best way they inform it, within the mid-1800s, their great-great-great grandfather Gullu Celebi set out for the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. On his approach, he traveled in a caravan passing the cities Aleppo and Damascus in Syria, the place he seen outlets promoting a walnut-filled model of the pastry.

Recent baklava sits on a windowsill at Gulluoglu.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Again in his hometown, then often known as Antep, baklava had been primarily made at residence. However seeing these Syrian shops led Gullu Celebi to cook dinner up a marketing strategy.

“Once they come again to Antep they made the model they’d seen within the shops in Aleppo and Damascus, however over time and with their expertise, and with utilizing native substances from Antep, they created the Gaziantep baklava we all know right this moment,” Murat Gullu says.

They developed a model with thinner layers, used sugar syrup as an alternative of honey and molasses and finally pistachios as an alternative of walnuts, he explains, “as a result of there was an abundance of pistachios out there right here, whereas walnuts got here [from] close by cities,” he explains.

Finally, professor Bayram says, the Gaziantep baklava identified right this moment was formed by the native substances, the ambiance and local weather of the town — and by native cooks who had been consumed with perfecting the recipe and handed that obsession alongside to their apprentices.

“There are 4 key substances: durum wheat flour, clarified butter [ghee] from sheep milk yogurt, sugar, and pistachios which are harvested a month earlier than maturing, when their oil content material is excessive and their shade is daring inexperienced and taste is powerful and candy,” Bayram says.

Murat (left) and Cevdet Gullu are homeowners of Gulluoglu and say they’re the sixth era of a baklava-making household in Gaziantep.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

“The many years of growing baklava reached its peak in 1940,” says Murat Gullu. “And that is the recipe we’re utilizing right this moment.”

A plate carrying 4 sorts of baklava seems. There’s the diamond-shaped basic; a bright-green dolama, by which a layer of phyllo is full of pistachio mud and rolled; sobiyet, which is sort of a turnover overflowing with pistachios; and eventually, bulbul yuvasi, meant to seem like a fowl’s nest, with out filling however with a beneficiant sprinkling of uncooked pistachio mud on high.

Earlier than taking a chunk, the hosts say to odor it.

“You possibly can odor the clarified butter, the pistachios and the dough all collectively,” says Bayram.

There is a particular strategy to eat it too — by holding it the wrong way up. “In order that the syrupy backside half hits the roof of your mouth, and the flakey crust falls in your tongue. In any other case the skinny crust will persist with the roof of the mouth,” says Murat Gullu.

It seems, correct Gaziantep baklava has a sound, too.

4 several types of baklava are served at Gulluoglu.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

“While you chunk into it or break a bit off along with your fork, you need to hear the sound huhsh — meaning the baklava layers are skinny. If it makes a cracking sound like, ‘chuht,’ it means the dough is thick, and that is not Gaziantep baklava,” Gullu says.

On the primary chunk of the basic diamond baklava — holding it the wrong way up, after all — that sound is evident, and sensations surge. It is shocking how the morsel dissolves in your tongue, with out hardly chewing. The flavors of roasted ghee and daring, shiny pistachios are a delight. And you are feeling a punch from the sugar, which the consultants say is critical for the structural integrity of the pastry.

Every of the 4 varieties provides its personal expertise, from style to texture, though the substances are the identical.

It isn’t simply the baklava-makers who’re obsessive about the pastry.

“Baklava has a major ceremonial and cultural function on this metropolis,” says Cevdet Gullu. “We take it to engagements, weddings, funerals. It is the final word reward and memento. Not a aircraft flies from right here that is not carrying a number of containers of baklava. We get guests from throughout Turkey and all around the world.”

With a contemporary twist: Celebiogullari

Bakers roll and stretch dough into paper-thin sheets for baklava on the manufacturing facility of Celebiogullari.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

It is time to see how baklava is made. The tour heads to the manufacturing facility of Celebiogullari, a more recent baklava-maker. Its founder Mehmet Ciftci apprenticed for years working with the highest baklava masters. “It takes not less than eight years to discover ways to make baklava,” Ciftci says.

He’s doing one thing a bit totally different right here: The baklava he makes is much less candy, he has performed round with a number of the shapes, and even makes a gluten-free model and a vegan one, with coconut butter as an alternative of ghee.

Contained in the manufacturing facility, it’s a sight to behold. It virtually appears like a cross between a navy facility and a home of worship. Ninety boys and males are hustling at their stations. There’s an entire fleet stretching out the dough in order that it is thinner than paper, silky and see-through. The air is roofed in white mud of flour and starch. There’s an individual whose solely job is to splash ghee between layers of filo dough. One other spreads the thinnest layer of cream. One other handles the pistachio filling. And on it goes till a tray of baklava is able to be baked in an oakwood-fired stone oven.

A baker rolls chopped pistachios into baklava dough on the Celebiogullari manufacturing facility.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

Boys as younger as 10 are shuffling round, carrying trays of flour, starch and pistachios — undistracted by this reporting group’s presence. They’re a part of an apprenticeship program that provides them college credit score and a certificates in the event that they select to open their very own baklava store sooner or later. Right here, they do not solely discover ways to make baklava, but in addition self-discipline and etiquette.

“That is how we preserve this commerce alive,” Ciftci says. “After I was 7 years previous, my mom despatched me to be taught from baklava cooks, and after we misbehaved or made errors they’d hit us with sticks. However right this moment, we’re instructing the younger ones to like the commerce.”

Instagram-worthy, however legit: Kocak

Subsequent on the tour is Kocak, which has turn out to be the most important identify in Gaziantep baklava, identified throughout Turkey and overseas. It feels glitzy and glamorous right here, and positively a vacationer hotspot. However when NPR meets the proprietor and chef Coskun Kocak, it turns into clear that there’s one other degree of baklava-obsessed grasp chef.

“We continue to grow, in actual fact we won’t cease it. There’s a enormous demand for actual Gaziantep baklava,” Kocak says.

The model’s large progress and success weigh on Kocak, who says he’s saved up at evening worrying over the standard and way forward for baklava making. He is important of the numerous mass-producing baklava makers within the metropolis who use machines as an alternative of people.

Kocak, a glitzy vacationer hotspot, has turn out to be the most important identify in Gaziantep baklava.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

“There are tons of of baklava-makers in Gaziantep,” Kocak says. “However you will not discover greater than 5 who’re making it the proper approach, the unique approach.”

“Making baklava is an artwork, and it is underneath risk,” Kocak says. He is speaking about modernization and local weather change, each of that are affecting the standard of the important thing uncooked substances.

With trendy methods, farmers have discovered easy methods to harvest the pistachios yearly as an alternative of the normal every-other-year cycle, he explains. “However that adjustments the style of the pistachio, every year it turns into much less and fewer scrumptious,” Kocak says. “The identical goes for our ghee, which is produced from the milk of sheep grazing on native endemic crops, however the space for his or her grazing is shrinking every year.”

Kocak desires to maintain the corporate’s progress in verify, resisting calls to open a second department. He says he is dedicated to sustaining Gaziantep’s authentic technique of creating baklava, which he sees as good.

“When you have even the slightest change in ingredient high quality, it will not be Antep baklava anymore,” Kocak says.

The place Syrian and Turkish traditions meet: Mahrouseh

The ultimate cease on this baklava crawl is to a store referred to as Mahrouseh, run by a Syrian refugee household from Aleppo, who had a sweets store again residence, and needed to flee to Turkey when the Syrian civil warfare broke out.

Turkey is internet hosting the biggest variety of Syrian refugees on the planet, some 3 million based on the United Nations. Lots of them have settled in Gaziantep, simply 60 miles from Aleppo.

Mahrouseh is a Syrian-owned candy store in Gaziantep. Turkey is internet hosting the biggest variety of Syrian refugees on the planet, some 3 million based on the United Nations.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

One noticeable distinction at this retailer, professor Mustafa Bayram factors out, is there are various sorts of desserts being bought right here, from desserts, cookies, baklava and varied different Syrian sweets.

“In Gaziantep, sometimes a baklava store solely has baklava. If you’d like desserts or different issues you must go some place else,” Bayram says. “This can be a great point that Syrians have introduced from their very own tradition to this metropolis.”

“When you’re solely going to do one factor, you must be very assured in it,” says Abdulrahman Hallaq with fun, as he serves prospects. “We like to supply our prospects a range they’ll select from.”

A few of the variations are apparent. The store’s baklava appears to be like drier and extra structured than the opposite Antep counterpart. The feel is crunchy and chewy and the style is much less candy.

However there may be not less than one similarity. “They’re utilizing Turkish pistachios as an alternative of Syrian ones,” Bayram says, declaring the colour. Certainly, the pistachios are Gaziantep’s trademark shiny inexperienced.

“Due to restrictions on pistachio imports in Turkey, they’d to make use of native ones as an alternative of the Syrian pistachio which has a extra yellow hue and a special style,” Bayram says.

Mahrouseh’s baklava appears to be like drier and extra structured than the opposite specimens in Gaziantep. Its texture is crunchy and chewy and the style is much less candy.

Claire Harbage/NPR

conceal caption

toggle caption

Claire Harbage/NPR

“We use much less syrup, in comparison with the native baklava, and since we’re making it right here and never in Syria, it does find yourself tasting fairly totally different from those we had in Syria,” Hallaq says. “However it’s a very good factor.”

“We [Turks] realized from them [Syrians] they usually realized from us,” Bayram says.

“Similar to how centuries in the past, when nice cuisines had been shaped by cross-cultural interactions, we live it once more right this moment. When Syrian refugees return residence, they are going to take again what they realized from us and we are going to use what they left for us right here.”

“And maybe 10, 20 years from now there shall be a brand new meals tradition born out of this coexistence,” Bayram says.

And who is aware of what varieties of latest and scrumptious recipes shall be found then.