Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaZambia’s infamous “black mountains” – big heaps of mining waste that scar the Copperbelt skyline – are deeply private to Stary Mwaba, one of many nation’s main visible artists.

“As children, we used to name it ‘mu hazard’ – which means ‘within the hazard’,” Mwaba tells the BBC.

“The ‘black mountain’ was this place the place you should not go,” says the painter, who was born and lived within the Copperbelt till he was 18.

“However we might sneak in anyway – to choose the wild fruits that by some means managed to develop there,” the artist remembers.

These days, the younger males heading to “mu hazard” are in search of fragments of copper ore within the stony slag of those towering dumpsites – the poisonous legacy of a century of business mining manufacturing in Zambia, one of many world’s largest copper and cobalt producers.

They dig deep and meandering tunnels – and hew out rocks to promote to largely Chinese language consumers, who then extract copper.

It’s powerful, harmful, usually unlawful and generally deadly work. But it surely will also be profitable – and, in a area the place youth unemployment is about 45%, for some younger individuals it’s the solely manner that they’ll make ends meet.

Stary Mwaba

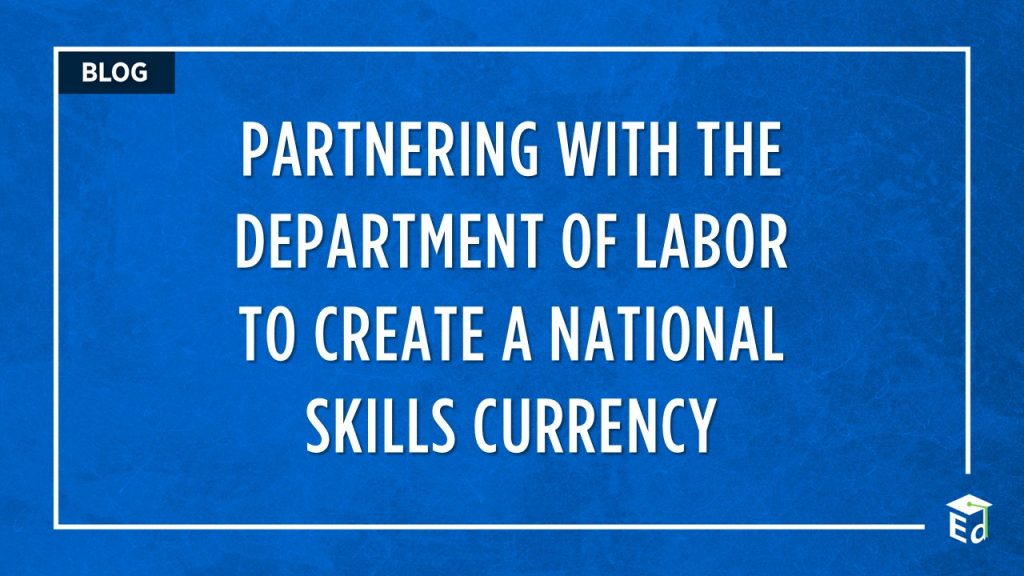

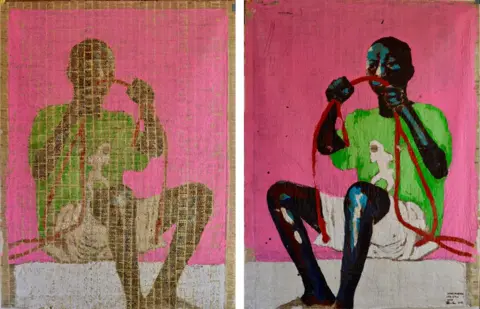

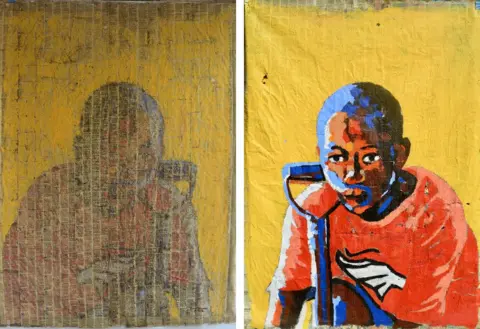

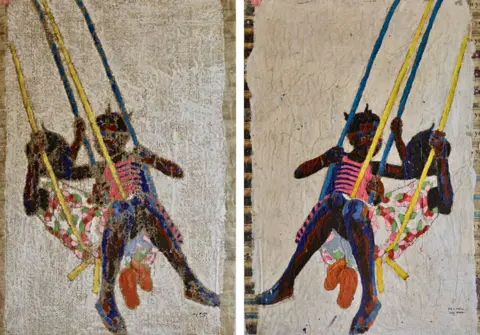

Stary MwabaMwaba’s newest work – on present on the Lusaka Nationwide Museum this month – tells the story of the younger individuals who mine the black mountain within the city of Kitwe – and captures the rhythms of life among the many residents of the Wusakile neighbourhood.

They work for gang masters generally known as “jerabos”, a corruption of “jail boys” – hinting at their perceived criminality.

The artist has painted a sequence of huge portraits, utilizing outdated newspapers as a canvas. He cuts out articles that seize his consideration – what he refers to as “grand narratives” – and sticks them on to a backing paper.

He makes use of a soldering gun to burn away among the phrases and create a sequence of perforations within the tales. Then he pours in paint to create the portraits, or what he calls the “little narratives”.

“I take these grand narratives, and I create holes to be able to’t make sense of the tales any extra. I then impose pictures of individuals I do know on to them – to point out that little tales, the little narratives of unusual individuals additionally rely,” Mwaba explains.

“They’ve tales which are vital and are a part of the larger story.”

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaThe portraits might be seen from either side and, in attribute Mwaba fashion, are brightly colored.

The artworks are coated with a clear acrylic and the borders of newspaper held along with clear tape as a result of they’re very fragile – just like the existence of the individuals Mwaba has painted.

They reside within the shadow of the black mountain – the location because the early Thirties of thousands and thousands of tonnes of waste, stuffed with poisonous heavy metals – which wreaks havoc on individuals’s well being and the atmosphere.

One portray from his present work is entitled Jerabo and exhibits a miner getting ready security ropes which are tied round his waist as he lowers himself down slim precarious tunnels, dug out by hand and susceptible to landslides.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaEarlier this 12 months, the complete water provide to Kitwe, dwelling to about 700,000 individuals, was shut down after a catastrophic spill of waste from a close-by Chinese language-owned copper mine into the streams that circulation via neighbourhoods like Wusakile into certainly one of Zambia’s most vital waterways, the Kafue River.

Mwaba hears tales of hardship and survival in the course of the drawing, pictures and efficiency workshops that he and different artists have held over a number of years.

Shofolo portrays a younger man virtually hugging his valuable “shofolo” – the Zambian English, or Zamglish, phrase for shovel. Such instruments are “a private lifeline”, Mwaba says.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaIpenga captures the tuba participant of an area church group as he parades via the streets one Sunday morning.

Most social lives in Wusakile revolve round both the church or the bar, Mwaba says.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaHowever the two younger women in Chimpelwa make their very own enjoyable on home-made swings.

Strung up within the sturdy branches of a tree are yellow and blue heavy-duty cables – as soon as high-voltage electrical cables, their copper wire innards have now been stripped out and offered as scrap steel.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaMwaba comes from a household of miners – his great-grandfathers and one grandfather labored down the mines and his father above the bottom.

However the 49-year-old’s curiosity within the affect of Zambia’s mining as a topic for his work started virtually unintentionally in about 2011 – after he helped his daughter, Zoe, with a science mission on the Chinese language Worldwide College, which she attended within the capital, Lusaka.

The duty was to exhibit how vegetation soak up minerals and water. He and Zoe went to the market and purchased a Chinese language cabbage. It’s not indigenous however is now eaten in lots of Zambian properties.

It has a white stem so is right to soak up the meals dyes that Zoe determined to make use of to point out how minerals can be equally drawn into the plant.

Mwaba remembers that the usage of Chinese language cabbage made the viewers “uneasy and so uncomfortable”.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaOn the time, the late Michael Sata was campaigning for the presidency – and tensions had been excessive due to his vitriolic rhetoric towards the Chinese language, who’re accused domestically of dominating the Zambian economic system and exploiting staff.

So Mwaba turned the science mission right into a murals – wherein he explored the Chinese language presence in Zambia’s mining sector via three Chinese language cabbage leaves, one dyed yellow to depict copper, one blue for cobalt and the third pink for manganese.

His Chinese language Cabbage introduced Mwaba a lot worldwide acclaim, and he returned to Zambia in 2015, glowing with the success of an artwork residency and exhibition in Germany.

He went to Kitwe, the place he had spent some childhood years. However his focus modified from simply exploring the Chinese language presence in Zambia to making an attempt to inform the story of the black mountain individuals.

“I went again to a spot the place I grew up and issues had modified a lot,” the artist says, including that he “by no means, ever imagined that I’d see the type of the state of affairs I see now – the poverty”.

“It was a really emotional house and I used to be unhappy,” Mwaba says.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaMwaba had moved to Kasama in Northern Province in 1994, after his father immediately died. Three years later Zambia’s mines had been privatised – resulting in huge job losses and an unprecedented financial disaster within the Copperbelt.

The black mountain – all the time a supply of environmental and well being issues – now grew to become someplace to earn cash.

“The worst factor that occurred is when the black mountain was super-profitable, most of those younger individuals give up college.”

Unable to get a job wherever else, Mwaba’s cousin Ngolofwana joined a crew of jerabos. Day-after-day he wakes up and dangers his life simply to remain afloat and feed his household.

However even when the federal government has banned mining there, the dumpsite’s wealth is tightly managed by an aggressive hierarchy – with the highest, generally very rich, jerabos usually residing as much as their nickname.

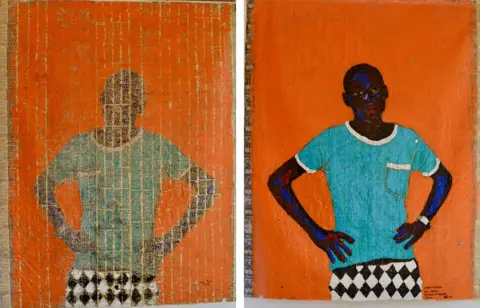

Frustrations additional down the jerabo chain – of feeling exploited, giving up on schooling to fund another person’s lavish life-style, and having little say in their very own futures – are mirrored within the portray of 1 younger man in a turquoise T-shirt standing along with his fingers confidently on his hips.

Stary Mwaba

Stary MwabaBoss for a Day got here out of a workshop wherein Mwaba invited individuals to take their very own pictures, putting a pose that mirrored their hopes and goals.

And sometimes Mwaba’s artwork might change the course of somebody’s life.

Mwaba remembers a time the place an older jerabo got here to a workshop and stated: “Hey, I actually like what you are doing.

“I believe I could not perceive it, nevertheless it’s greatest for my younger brother to be coming right here as a result of I do not need him to undergo what I went via.”

Penny Dale is a contract journalist, podcast and documentary-maker primarily based in London

Extra BBC tales on Zambia:

Getty Photographs/BBC

Getty Photographs/BBC