Geneva correspondent

BBC

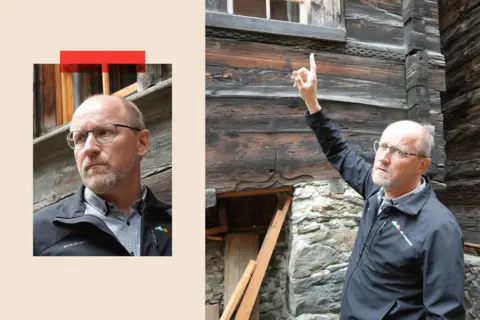

BBCIn a small village in Switzerland’s stunning Loetschental valley, Matthias Bellwald walks down the principle road and is greeted each few steps by locals who smile or supply a handshake or pleasant phrase.

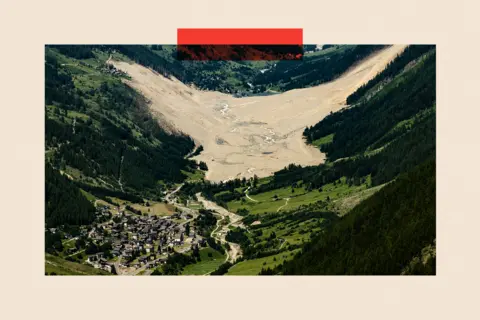

Mr Bellwald is a mayor, however this is not his village. Two months in the past his house, three miles away in Blatten, was wiped off the map when a part of the mountain and glacier collapsed into the valley.

The village’s 300 residents had been evacuated days earlier, after geologists warned that the mountain was more and more unstable. However they misplaced their properties, their church, their resorts and their farms.

Lukas Kalbermatten additionally misplaced the lodge that had been in his household for 3 generations.”The sensation of the village, all of the small alleys via the homes, the church, the recollections you had if you performed there as a toddler… all that is gone.”

Resort Edelweiss

Resort EdelweissImmediately, he’s residing in borrowed lodging within the village of Wiler. Mr Bellwald has a short lived workplace there too, the place he’s supervising the large clean-up operation – and the rebuild.

The excellent news is, he believes the location could be cleared by 2028, with the primary new homes prepared by 2029. But it surely comes with a hefty pricetag.

Rebuilding Blatten is estimated to price a whole bunch of hundreds of thousands of {dollars}, maybe as a lot as $1 million (USD) per resident.

Voluntary contributions from the general public shortly raised hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs to assist those that had misplaced their properties. The federal authorities and the canton promised monetary help too. However some in Switzerland are asking: is it value it?

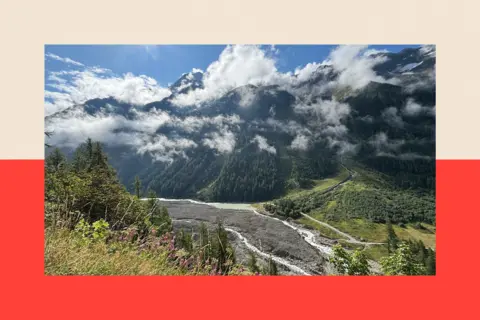

Shutterstock

ShutterstockAlthough the catastrophe shocked Switzerland, some two thirds of the nation is mountainous, and local weather scientists warn that the glaciers and the permafrost – the glue that holds the mountains collectively – are thawing as the worldwide temperature will increase, making landslides extra probably. Defending areas shall be expensive.

Switzerland spends virtually $500m a yr on protecting constructions, however a report carried out in 2007 for the Swiss parliament recommended actual safety in opposition to pure hazards might price six occasions that.

Is {that a} worthwhile funding? Or ought to the nation – and residents – actually take into account the painful possibility of abandoning a few of their villages?

The day the earth shook

The Alps are an integral a part of Swiss identification. Every valley, just like the Loetschental, has its personal tradition.

Mr Kalbermatten used to take delight in exhibiting lodge friends the traditional wood homes in Blatten. Generally he taught them a couple of phrases of Leetschär, the native dialect.

Dropping Blatten, and the prospect of shedding others prefer it, has made many Swiss ask themselves what number of of these alpine traditions might disappear.

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieImmediately, Blatten lies below hundreds of thousands of cubic metres of rock, mud, and ice. Above it, the mountain stays unstable.

Once they had been first evacuated, Blatten’s residents, figuring out their homes had stood there for hundreds of years, believed it was a purely precautionary measure. They might be house once more quickly, they thought.

Fernando Lehner, a retired businessman, says nobody anticipated the dimensions of the catastrophe. “We knew there can be a landslide that day… But it surely was simply unbelievable. I’d by no means have imagined that it will come down so shortly.

“And that explosion, when the glacier and landslide got here down into the valley, I am going to always remember it. The earth shook.”

Landslides are ‘extra unpredictable’

The individuals of Blatten, eager to get their properties again as quickly as doable, do not wish to speak about local weather change. They level out that the Alps are at all times harmful, and describe the catastrophe as a as soon as in a millennium occasion.

However local weather scientists say international warming is making alpine life extra dangerous.

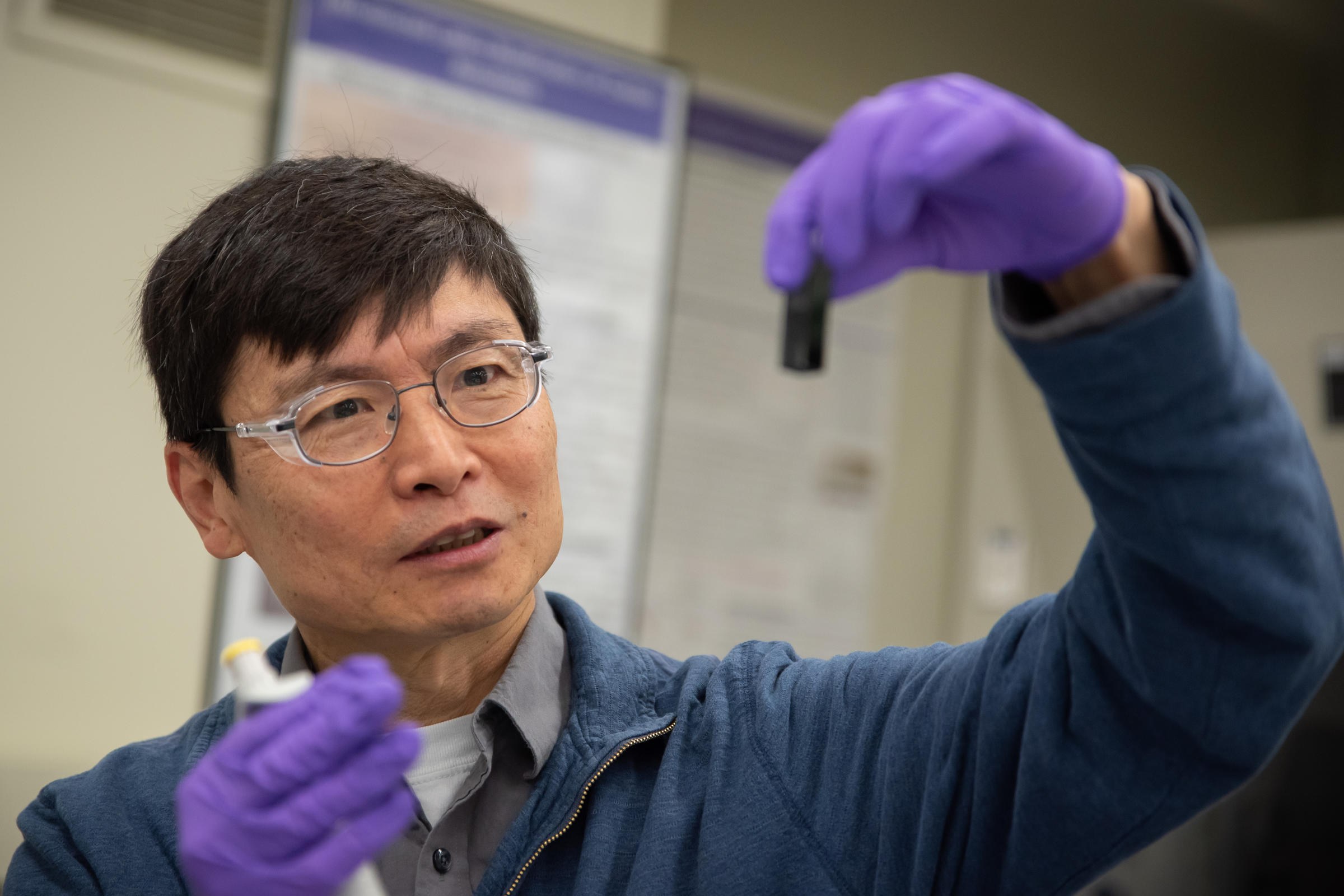

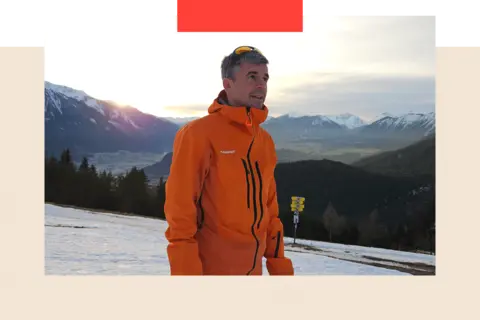

Matthias Huss, a glaciologist with Zurich’s Federal Institute of Expertise, in addition to glacier monitoring group Glamos, argues that local weather change was an element within the Blatten catastrophe.

“The thawing of permafrost at very excessive elevation led to the collapse of the summit,” he explains.

Matthias Huss

Matthias Huss“This mountain summit crashed down onto the glacier… and in addition the glacier retreat led to the truth that the glacier stabilised the mountain much less effectively than earlier than. So local weather change was concerned at each angle.”

Geological adjustments unrelated to local weather change additionally performed a job, he concedes – however he factors out that glaciers and permafrost are key stabilising elements throughout the alps.

His group at Glamos has monitored a document shrinkage of the glaciers over the previous few years. And common alpine temperatures are rising.

Within the days earlier than the mountain crashed down, Switzerland’s zero-degree threshold – the altitude at which the temperature reaches freezing level – rose above 5,000 metres, larger than any mountain within the nation.

“It’s not the very first time that we’re seeing massive landslides within the Alps,” says Mr Huss. “I believe what must be worrying us is that these occasions have gotten extra frequent, but in addition extra unpredictable.”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieA examine from November 2024 by the Swiss Federal Analysis Institute, which reviewed three a long time of literature, concurred that local weather change was “quickly altering excessive mountain environments, together with altering the frequency, dynamic conduct, location, and magnitude of alpine mass actions”, though quantifying the precise impression of local weather change was “troublesome”.

Extra villages, extra evacuations

Graubünden is the most important vacation area in Switzerland, and is in style with skiers and hikers for its untouched nature, alpine views and fairly villages.

The Winter Olympics was hosted right here twice – within the upmarket resort of St Moritz – whereas the city of Davos hosts world leaders for the World Financial Discussion board every year.

One village in Graubünden has a unique story to inform.

Brienz was evacuated greater than two years in the past due to indicators of harmful instability within the mountain above.

Its residents have nonetheless not been capable of return, and in July heavy rain throughout Switzerland led geologists to warn a landslide appeared imminent.

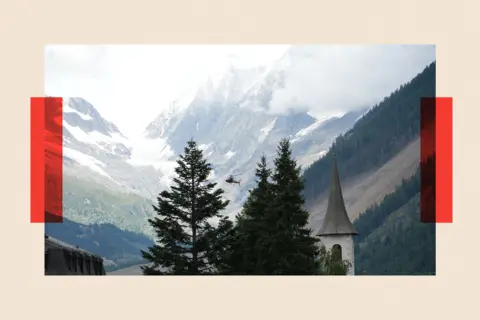

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieElsewhere in Switzerland, above the resort of Kandersteg, within the Bernese Oberland area, a rockface has turn out to be unstable, threatening the village. Now residents have an evacuation plan.

There too, heavy rain this summer season raised the alarm, and a few mountaineering trails as much as Oeschinen Lake, a well-liked vacationer attraction, had been closed.

Some disasters have claimed lives. In 2017, an enormous rockslide got here down near the village of Bondo, killing eight hikers.

Bondo has since been rebuilt, and refortified, at a value of $64 million. Way back to 2003, the village of Pontresina spent hundreds of thousands on a protecting dam to shore up the thawing permafrost within the mountain above.

Not each alpine village is in danger, however the obvious unpredictability is inflicting large concern.

The talk round relocation

Blatten, like all Swiss mountain villages, was danger mapped and monitored; that is why its 300 residents had been evacuated. Now, questions are being requested about the way forward for different villages too.

Within the aftermath of the catastrophe, there was an enormous outpouring of sympathy. However the doable price ticket of rebuilding it additionally got here with doubts.

An editorial within the influential Neue Zürcher Zeitung questioned Switzerland’s conventional – and constitutional – wealth distribution mannequin, which takes tax income from city centres like Zurich to help distant mountain communities.

The article described Swiss politicians as being “caught in an empathy entice”, including that “as a result of such incidents have gotten extra frequent on account of local weather change, they’re shaking individuals’s willingness to pay for the parable of the Alps, which shapes the nation’s identification.”

It recommended individuals residing in dangerous areas of the Alps ought to take into account relocation.

Preserving the alpine villages is dear. And Neue Zürcher Zeitung was not the primary to query the price of saving each alpine group, however its tone angered some.

Whereas three quarters of Swiss dwell in city areas, many have robust household connections to the mountains. Switzerland could also be a rich, extremely developed, high-tech nation now, however its historical past is rural, marked by poverty and harsh residing circumstances. Famine within the nineteenth century induced waves of emigration.

Mr Kalbermatten explains that the phrase “heimat” is vastly necessary in Switzerland. “Heimat is if you shut your eyes and you consider what you probably did as a toddler, the place you lived as a toddler.

“It is a a lot larger phrase than house.”

Ask a Swiss individual residing for many years in Zurich or Geneva, and even New York, the place their heimat is, and for a lot of, the reply would be the village they had been born in.

For Mr Kalbermatten and his sister and brothers, who dwell in cities, heimat is the valley the place individuals communicate Leetschär, the dialect all of them nonetheless dream in.

Imogen Foulkes

Imogen FoulkesThe concern is that if these valleys turn out to be depopulated, different elements of distinctive mountain tradition could possibly be misplaced too – just like the Tschäggättä, conventional wood masks, distinctive to the Loetschental valley.

Their origins are mysterious, probably pagan. Each February, native younger males put on them, together with animal skins, and run via the streets.

Mr Kalbermatten factors to the instance of some areas of northern Italy the place this lack of tradition has occurred. “[Now] there are solely deserted villages, empty homes, and wolves.

“Do we would like that?”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieFor a lot of, the reply isn’t any: An opinion ballot from analysis institute, Sotomo, requested 2,790 individuals what they most cherished about their nation. The commonest reply? Our stunning alpine panorama, and our stability.

However the ballot didn’t ask what value they had been ready to pay.

Attempting to tame a mountain

Boris Previsic, the director of the College of Lucerne’s Institute for the Tradition of the Alps, says that many Swiss, no less than within the cities, had begun to consider they’d tamed the alpine setting.

Switzerland’s railways, tunnels, cable automobiles and excessive alpine passes are masterpieces of engineering, connecting alpine communities. However now, partly due to local weather change, he suggests, that confidence is gone.

“The human induced geology is just too robust in comparison with human beings,” he argues.

“In Switzerland, we thought we might do every part with infrastructure. Now I believe we’re at floor zero regarding infrastructure.”

Boris Previsic

Boris PrevisicThe village of Blatten had stood for hundreds of years. “When you find yourself in a village which has existed already for 800 years, it is best to really feel protected. That’s what is so stunning.”

In his view, it’s time to combat in opposition to these villages dying out. “To combat means we now have to be extra ready,” he explains. “However we now have to be extra versatile. Now we have at all times additionally to contemplate evacuation.”

On the finish of the day, he provides, “you can not maintain again the entire mountain”.

Within the village of Wiler, Mr Previsic’s level is greeted with a weary smile. “The mountain at all times decides,” agrees Mr Bellwald.

“We all know that they’re harmful. We love the mountains, we do not hate them due to that. Our grandfathers lived with them. Our fathers lived with them. And our kids will even dwell with them.”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieAt lunchtime within the native restaurant in Wiler, the tables are full of clean-up groups, engineers and helicopter crew. The Blatten restoration operation is in full swing.

At one desk, a person from one in every of Switzerland’s largest insurance coverage firms sits alone. Each half hour, he’s joined by somebody, an aged couple, a center aged man, a younger girl. He buys every a drink, and punctiliously notes down the small print of their misplaced properties.

Exterior, alongside the valley’s winding roads, lorries and bulldozers trundle as much as the catastrophe website. Overhead, helicopters carry giant chunks of particles. Even the army is concerned.

Sebastian Neuhaus instructions the Swiss military’s catastrophe aid readiness battalion, and says they have to press on regardless of the dimensions of the duty. “Now we have to,” he says. “There are 300 life histories buried down there.”

The abiding feeling is one in every of cussed willpower to hold on. “If we see somebody from Blatten, we hug one another,” says Mr Kalbermatten.

“Generally we are saying, ‘it is good, you are still right here.’ And that is an important factor, we’re all nonetheless right here.”

Lead picture: The village of Blatten after the catastrophe. Credit score: EPA / Shutterstock

BBC InDepth is the house on the web site and app for the very best evaluation, with contemporary views that problem assumptions and deep reporting on the most important problems with the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content material from throughout BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You possibly can ship us your suggestions on the InDepth part by clicking on the button beneath.