BBC World Service

Adil Amin Akhoon

Adil Amin AkhoonWithin the quiet, slim lanes of Srinagar in Indian-administered Kashmir, a small, dimly lit workshop stands as one of many final holdouts of a vanishing craft.

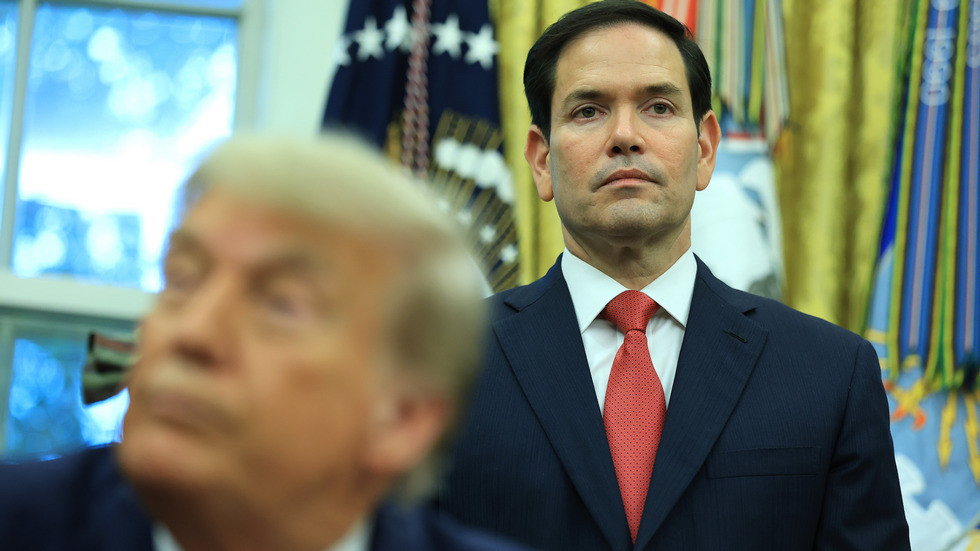

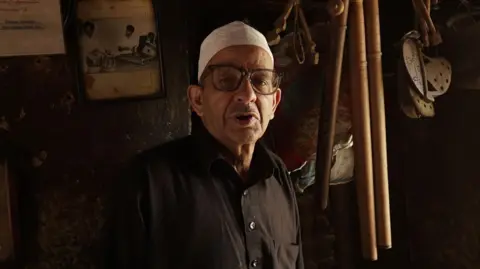

Contained in the store sits Ghulam Mohammed Zaz, who’s broadly believed to be the area’s final artisan who could make the santoor by hand.

Santoor is a trapezoid-shaped stringed musical instrument, much like a dulcimer, which is performed with mallets. It’s recognized for its crystalline bell-like tone and has been Kashmir’s musical signature for hundreds of years.

Mr Ghulam Mohammed belongs to a lineage of craftsmen who’ve been constructing string devices in Kashmir for over seven generations. The Zaz household title has lengthy been synonymous because the makers of the santoor, rabab, sarangi and sehtar.

However lately, the demand for handcrafted devices has dwindled, changed by machine-made variations which are cheaper and faster to provide. On the similar time, music tastes have modified, including to the decline.

“With hip hop, rap, and digital music now dominating Kashmir’s soundscape, youthful generations not join with the depth or self-discipline of conventional music,” says Shabir Ahmad Mir, a music trainer. Because of this, demand for the santoor has collapsed, leaving craftsmen with out apprentices or a sustainable market, he provides.

Adil Amin Akhoon

Adil Amin AkhoonIn his century-old store, Mr Ghulam Mohammed sits beside a hole block of wooden and worn iron instruments – the quiet remnants of a fading custom.

“There is no such thing as a one left [to continue the craft],” he says. “I’m the final.”

However it wasn’t at all times this fashion.

Over time, famend Sufi and people artists have performed santoors handcrafted by Mr Ghulam Mohammed.

A photograph in his store exhibits maestros Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori performing together with his devices.

Believed to have originated in Persia, the santoor reached India within the thirteenth or 14th century, spreading by way of Central Asia and the Center East. In Kashmir, it took on a definite identification, turning into central to Sufi poetry and people traditions.

“Initially a part of Sufiana Mausiqi (an ensemble music custom), the santoor had a mushy, folk-like tone,” says Mr Mir.

Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma later tailored it for Indian classical music, he says, by including strings, redesigning bridges for richer resonance and introducing new taking part in strategies.

Bhajan Sopori, who has Kashmiri roots, “deepened its tonal vary and infused it with Sufi expression”, provides Mr Mir, serving to cement the santoor’s place in Indian classical music.

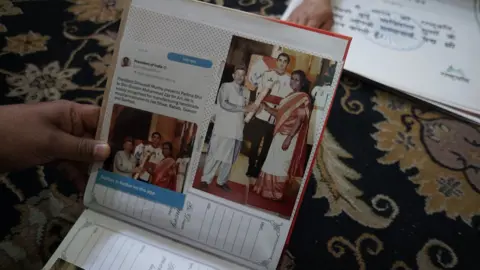

One other photograph exhibits Mr Ghulam Mohammed receiving the Padma Shri from President Droupadi Murmu in 2022, honoured for his craftsmanship with India’s fourth-highest civilian award.

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesMr Ghulam Mohammed was born within the Forties in Zaina Kadal, a neighbourhood named after an iconic bridge that when served because the lifeline of commerce and tradition in Kashmir. Rising up, he was surrounded by the sounds and instruments of his household’s commerce.

Well being points pressured him to depart formal schooling at an early age and that’s when he started studying the artwork of santoor-making from his father and grandfather – each grasp craftsmen themselves.

“They taught me not simply easy methods to make an instrument however easy methods to hear – to the wooden, the air and the fingers that may play it,” he mentioned.

“My ancestors was summoned by the courts of native kings and had been typically requested to construct devices that might soothe hearts,” he says.

In his workshop, a picket bench lined with chisels and strings lies beside the skeletal body of an unfinished santoor. The air smells faintly of aged walnut wooden, however there isn’t any equipment in sight.

Mr Ghulam Mohammed believes machine-made devices lack the heat and depth of these crafted by hand and the audio high quality comes nowhere shut.

Making a santoor is a sluggish, deliberate course of, the craftsman says. It begins with choosing the correct wooden, aged and seasoned for not less than 5 years. The physique is then carved and hollowed for optimum resonance, and every of the 25 bridges is exactly formed and positioned.

Over 100 strings are added, adopted by the painstaking tuning course of, which may take weeks and even months.

“It’s the craft of persistence and perseverance,” he says.

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesLately, social media influencers have visited Mr Ghulam Mohammed’s workshop, sharing its story on-line. He appreciates the eye however says it hasn’t led to actual efforts to protect the craft or its legacy.

“These are good folks,” he says, “however what’s going to turn out to be of this place when I’m gone?”

Along with his three daughters pursuing different careers, there is not any one within the household to hold on his work. Over time, he is had gives – authorities grants, guarantees of apprentices, even options from the state handicrafts division.

However Mr Ghulam Mohammed says he is “not on the lookout for fame or charity”. What he really desires is somebody to hold the artwork ahead.

Now in his eighties, he typically spends hours beside an unfinished santoor, listening to the silence of what is but to be accomplished.

“This isn’t simply woodwork,” he says.

“It’s poetry. A language. A tongue I give to the instrument.

“I hear the santoor earlier than it performs. That’s the secret. That’s what have to be handed on,” he provides.

Because the world exterior embraces modernity, Mr Ghulam Mohammed’s workshop stays untouched by time – sluggish, silent and stuffed with the scent of walnut and reminiscence.

“Wooden and music,” he says, “each die for those who do not give them time.”

“I need somebody who really loves the craft to take it ahead. Not for the cash, not for the cameras, however for the music.”

Comply with BBC Information India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Fb.