On a sun-drenched morning off the coast of Villefranche-sur-Mer, the Sagitta III cuts by the cobalt waters of the Mediterranean, previous the quiet marinas and pine-fringed terraces of France’s Côte d’Azur. The 40-foot scientific vessel – named after a fearsome zooplankton with hook-lined jaws – rumbles towards a lonely yellow buoy bobbing offshore.

Within the distance, the resort city shimmers, a mirage of pastel villas and church towers clinging to the cliffs. However aboard the Sagitta III, the romance ends on the rail. Lionel Guidi, an area scientist on the Villefranche Oceanography Lab — identified, with becoming Frenchness, by its acronym LOV — friends into the ocean with a practiced depth.

He’s right here to fish plankton.

Round him, a veteran crew strikes with precision, beneath the iron fist of Captain Jean-Yves Carval. “Plankton is fragile,” cautions the rugged seaman, who’s spent almost 50 years navigating freighters, trawlers – and now, scientific boats. “In the event you go too quick, you make compote.”

The craft slows because it reaches the buoy, a sampling web site the place Guidi and his LOV colleagues have gathered marine information day-after-day for many years. Beneath deck, the boat’s bearded chief mechanic, Christophe Kieger, readies a big winch. Its 12,000-foot cable unfurls, sending a fine-meshed internet – every pore no wider than a grain of salt – drifting towards the deep. Slowly, it sinks to 250 toes.

Minutes later, the web resurfaced, heavy with a brownish, gelatinous goo.

“There’s life!” cries Anthéa Bourhis, a 28-year-old technician from Brittany, as she rigorously transfers the contents right into a plastic bucket.

Certainly, that catch holds greater than seawater and slime. It’s the uncooked materials of the planet’s previous – and maybe its future.

A worrisome development

Plankton type the beating coronary heart of the ocean’s engine. These tiny organisms soak up carbon dioxide, launch oxygen, and underpin your complete marine meals internet. With out them, life as we all know it will not exist.

However what’s plankton?

It’s not a single creature, however an enormous solid of marine nomads, all certain by one trait: they’ll’t swim in opposition to the present. They drift with tides and eddies, using invisible flows that govern their lives. Some aren’t any greater than a speck of mud; others, like jellyfish, can stretch greater than a meter broad.

There are two foremost varieties. People who harness daylight: phytoplankton — microscopic marine crops that photosynthesize like greenery on land and, over geological time, have produced greater than half the oxygen we breathe. And people who feed: zooplankton — tiny animals that graze on their plant-like cousins, hunt one another, and themselves turn out to be prey, sustaining fish, whales, and seabirds alike.

On the Villefranche Oceanography Lab, scientists have been monitoring these creatures for many years. Their every day sampling, carried out just some miles offshore, has yielded one of many longest steady data of plankton on the earth.

And that document is now displaying indicators of stress.

“At our commentary web site, floor temperatures have risen by about 1.5 levels Celsius over the past 50 years,” Lionel Guidi tells UN Information. “We’ve seen a basic drop in phytoplankton main manufacturing.”

The implications might doubtlessly be far-reaching. Phytoplankton type the muse of the marine ecosystem, and a decline of their numbers may set off a cascading impact, disrupting zooplankton, fish shares, and ocean biodiversity as a complete. It might additionally weaken their means to soak up carbon dioxide, drawing it from the ambiance and carrying it into the deep – what scientists name ‘the organic pump’, considered one of Earth’s most significant pure local weather regulators.

Tiny aliens

Again on the LOV, with the Sagitta III now resting in its berth, Lionel Guidi gestures towards the day’s pattern. “The whole lot begins with plankton,” says the scientist, who, earlier than touchdown in Villefranche, performed marine analysis in Texas and Hawaii.

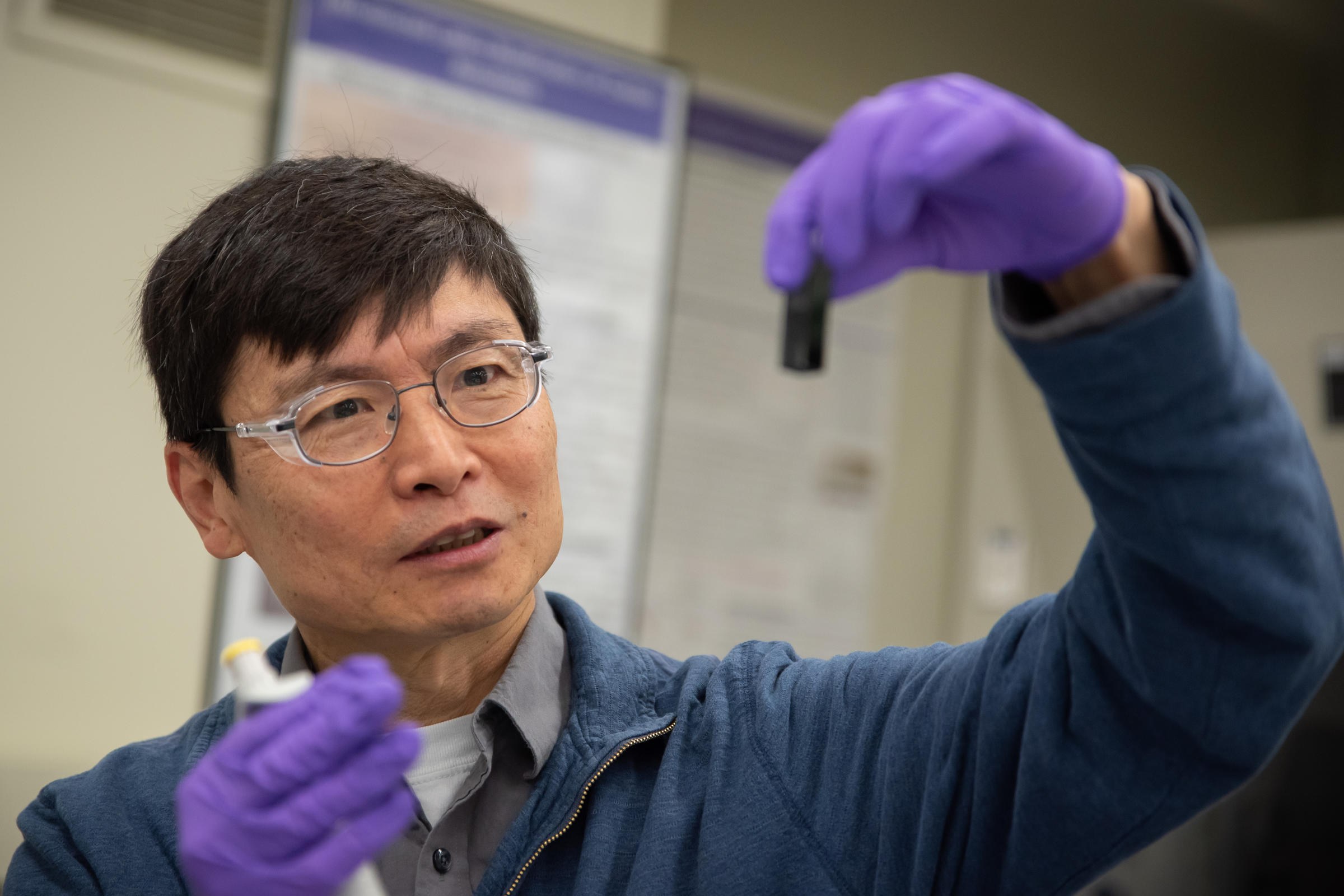

In the meantime, Anthéa Bourhis, the younger technician, has donned a white lab coat and is bent over the morning’s catch. She fixes the pattern in formaldehyde, a step that can retailer the zooplankton but in addition kill them. “In the event that they transfer, it messes with the scan,” she explains.

As soon as morbidly nonetheless, the small animals are fed right into a scanner. Slowly, shapes blossom on Bourhis’s display screen, as improbably sleek copepods – translucent and shrimp-like, with feathery antennae – float into view.

“We’ve received some handsome ones,” she says, grinning.

She begins transferring the digital photos into an AI-operated database able to sorting zooplankton by group, household, and species.

“They’ve appendages all over the place,” provides Lionel Guidi. “Arms pointing in all instructions.”

Considered one of these deep-sea creatures, known as Phronima, even impressed the monster in Ridley Scott’s 1979 movie Alien. “You look by the microscope,” Guidi says, “and there’s a complete world.”

From science to coverage

A world that’s altering – and never quick sufficient to be understood by satellites or snapshots. That’s why LOV’s long-term collection issues: it captures tendencies that span years and even a long time, serving to scientists distinguish pure cycles from climate-driven shifts.

“After we clarify that if there’s no extra plankton, there’s no extra life within the ocean. And if there’s no extra life within the ocean, life on land gained’t final for much longer both, then abruptly folks turn out to be much more keen on why defending plankton issues,” stated Jean-Olivier Irisson, one other plankton specialist on the LOV.

Subsequent week, simply quarter-hour down the coast, town of Good is internet hosting the third UN Ocean Convention (UNOC3) – a five-day summit bringing collectively scientists, diplomats, activists, and enterprise leaders to chart the course for marine conservation.

Among the many gathering’s priorities: advancing the ‘30 by 30’ pledge to guard 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030 and bringing the landmark Excessive Seas Treaty, or ‘BBNJ accord’ to safeguard life in worldwide waters, nearer to ratification.

Guidi underscored the urgency of those UN-led efforts, saying: “All of this have to be thought by with people who find themselves able to making legal guidelines, however based mostly on scientific reasoning.”

He doesn’t declare to write down coverage himself. However he is aware of the place science suits. “We convey scientific outcomes; now we have proof of a phenomenon. These usually are not opinions, they’re information.”

And so, in Villefranche, Lionel Guidi, Anthéa Bourhis and Captain Carval proceed their work – hauling life from the ocean, capturing it in pixels, counting its limbs, and sharing its information with scientists throughout the globe. In doing so, they chart not only a threatened ocean, however the unseen threads that bind life itself.