BBC

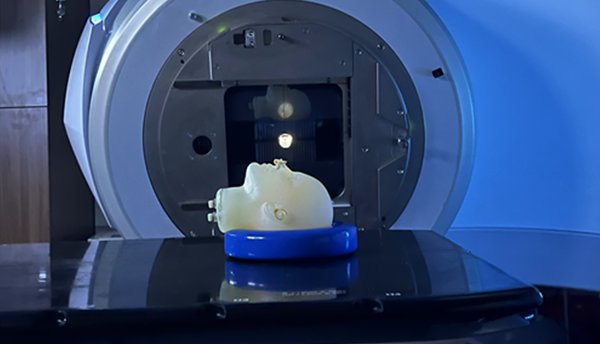

BBC“These,” says Dr Anas al-Hourani, “are from a combined mass grave.”

The pinnacle of the newly-opened Syrian Identification Centre is standing subsequent to 2 tables, coated in femurs. There are 32 of the human thigh bones on every laminated white tablecloth. They’ve been neatly aligned and numbered.

Sorting is the primary process for this new hyperlink within the lengthy chain from crime to justice in Syria. A “combined mass grave” signifies that corpses had been thrown one on prime of one other.

The probabilities are, these bones belong to a number of the a whole lot of 1000’s believed to have been killed by the regimes of the ousted president Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, who collectively dominated Syria for greater than 5 a long time.

In that case, says Dr al-Hourani, they had been among the many newer victims: they died not more than a 12 months in the past.

Dr al-Hourani is a forensic odontologist: tooth can let you know a lot extra a few physique, he says, no less than relating to figuring out who the particular person was.

However with a femur the lab employees within the basement of this squat gray workplace constructing in Damascus can start the duty: they’ll study the peak, the intercourse, the age, what kind of job they’d; they may additionally be capable of see whether or not the sufferer was tortured.

The gold commonplace in identification is after all DNA evaluation. However, he says, there is only one DNA testing centre in Syria. Many had been destroyed through the nation’s civil struggle. And “due to sanctions, a number of the precursor chemical substances that we’d like for the checks are presently not obtainable”.

They’ve additionally been knowledgeable that “components of the devices could possibly be used for aviation and so for navy functions”. In different phrases, they could possibly be deemed “twin use”, and so proscribed by many Western international locations from export to Syria.

Add to that, the price: $250 (£187) for a single take a look at. And, says Dr al-Hourani, “in a combined mass grave, it’s a must to do about 20 checks to collect all of the components of 1 physique”. The lab depends completely on funding from the Worldwide Committee of the Purple Cross.

The brand new authorities of Islamist rebels-turned-rulers says that what they name “transitional justice” is considered one of their priorities.

Many Syrians who’ve misplaced family members, and misplaced all hint of them, have instructed the BBC that they continue to be unimpressed and annoyed: they need to see extra effort from the individuals who lastly chased Bashar al-Assad from energy final December after 13 years of struggle.

Throughout these lengthy years of battle, a whole lot of 1000’s had been killed, and tens of millions displaced. And, by one estimate, greater than 130,000 individuals had been forcibly disappeared.

On the present charge, it could actually take months to determine only one sufferer from a combined mass grave. “This,” says Dr al-Hourani, “would be the work of many, a few years.”

‘Mangled and tortured’ our bodies

Eleven of these “combined mass graves” are slung round a fantastic, barren hilltop outdoors Damascus. The BBC are the primary worldwide media to see this web site. The graves are fairly seen now. Within the years since they had been dug, their floor has sunk into the dry, stony earth.

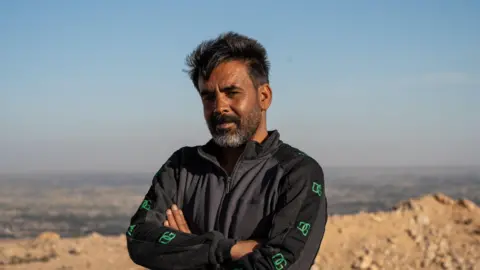

Accompanying us is Hussein Alawi al-Manfi, or Abu Ali, as he additionally calls himself. He was a driver within the Syrian navy. “My cargo,” says Abu Ali, “was human our bodies.”

This compact man with a salt and pepper beard was tracked down due to the tireless investigative work of Mouaz Mustafa, the Syrian-American government director of the Syrian Emergency Job Power, a US-based advocacy group. He had persuaded Abu Ali to hitch us, to bear witness to what Mouaz calls “the worst crimes of the twenty first Century”.

Abu Ali transported lorry a great deal of corpses to a number of websites for greater than 10 years. At this location, he got here, on common, twice every week for roughly two years at the beginning of the demonstrations after which the struggle, between 2011 and 2013.

The routine was all the time the identical. He’d head to a navy or safety set up. “I had a 16m (52ft) trailer. It wasn’t all the time stuffed to the brim. However I might have, I suppose, a mean of 150 to 200 our bodies in every load.”

Of his cargo, he says he’s satisfied they had been civilians. Their our bodies had been “mangled and tortured”. The one identification he might see had been numbers written on the cadaver or caught to the chest or brow. The numbers recognized the place they’d died.

There have been quite a bit, he stated, from “215” – a infamous navy intelligence detention centre in Damascus often called “Department 215”. It’s a place we’ll re-visit on this story.

Abu Ali’s trailer didn’t have a hydraulic raise to tip and dump his load. When he backed as much as a trench, troopers would pull the our bodies into the opening one after one other. Then a front-loader tractor would “flatten them out, compress them in, fill within the grave.”

Three males with weathered faces from a neighbouring village have arrived. They corroborate the story of the common visits by navy lorries to this distant spot.

And as for the person behind the wheel: how might he do that for week after week, 12 months after 12 months? What was he telling himself every time he climbed into his cab?

Abu Ali says he realized to be a mute servant of the state. “You may’t say something good or unhealthy.”

Because the troopers dumped the corpses into the freshly excavated pits, “I might simply stroll away and have a look at the celebrities. Or look down in direction of Damascus.”

‘They broke his arms and beat his again’

Damascus is the place Malak Aoude has not too long ago returned, after years as a refugee in Turkey. Syria might have been freed of the chokehold of the Assads’ dynastic dictatorship. Malak remains to be serving a life sentence.

For the previous 13 years, she has been locked right into a each day routine of ache and longing. It was 2012, a 12 months after a number of the individuals of Syria had dared to boost a protest in opposition to their president, that her two boys had been disappeared.

Mohammed was nonetheless an adolescent when he was conscripted into Assad’s military, because the demonstrations unfold and the regime’s lethal crackdown sparked a full-blown struggle.

He hated what he was seeing, his mom says. Mohammed began absconding, and even went on the demos himself. However he was tracked down.

“They broke his arms and beat his again,” says his mom. “He spent three days unconscious in hospital.”

Mohammed went AWOL once more. “I reported him lacking,” says Malak. “However I used to be hiding him.”

In Might 2012, 19-year-old’s Mohammed luck ran out. He was caught together with a bunch of buddies. They had been shot. Malak says there was no formal notification. However she has all the time assumed he was killed.

Six months later, Mohammed’s youthful brother Maher was dragged from faculty by officers. It was Maher’s second arrest. He’d gone to the protests in 2011, aged 14. That had led to his first arrest. When he was let loose of detention, a month later, he was in his underwear, coated, says his mom, in cigarette burns, wounds and lice. “He was terrified.”

Malak thinks Maher was disappeared from faculty in 2012 as a result of the authorities had discovered that she had been hiding his older brother. Now, for the primary time in 13 years, Malak returns to that college, determined to get any clue about what occurred to Maher.

The brand new headteacher produces a few battered pink ledgers. Malak traces the rows of names along with her finger, after which finds her son’s title. December 2012, the file flatly states: Maher has been excluded from faculty as a result of he has failed to show up for classes for 2 weeks.

There is no such thing as a rationalization that it’s the state which has disappeared him. There’s something else, although: a folder with Maher’s faculty information has been discovered. Its cowl is adorned with {a photograph} of a clever Bashar al-Assad, gazing thoughtfully into the space. Malak picks up a pen from the headteacher’s desk and scribbles over the photograph. Six months in the past, that gesture might have been deadly.

For years, the one scraps Malak needed to cling to had been two males who say they noticed Maher in “Department 215” – that very same navy detention centre which produced so many corpses for Abu Ali to move.

One of many witnesses instructed Malak that her boy had instructed him one thing about his dad and mom that, his mom says, solely he might have recognized. It was undoubtedly him. “He requested this man to inform me he was doing effective.” Malak heaves and leaks tears, stuffs a tattered tissue into the corners of her eyes.

For Malak, like so many Syrians, the autumn of Assad was not only a day of pleasure, however of hope. “I assumed there was a 90% likelihood Maher would stroll out of jail. I used to be ready for him.”

However she has not even been capable of finding her son’s title on the jail lists. And so the throb of ache continues to course by way of her. “I really feel misplaced and confused,” she says.

Her personal youthful brother, Mahmoud, had been killed by a tank firing on civilians in 2013.

“No less than he had a funeral.”